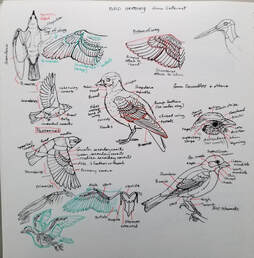

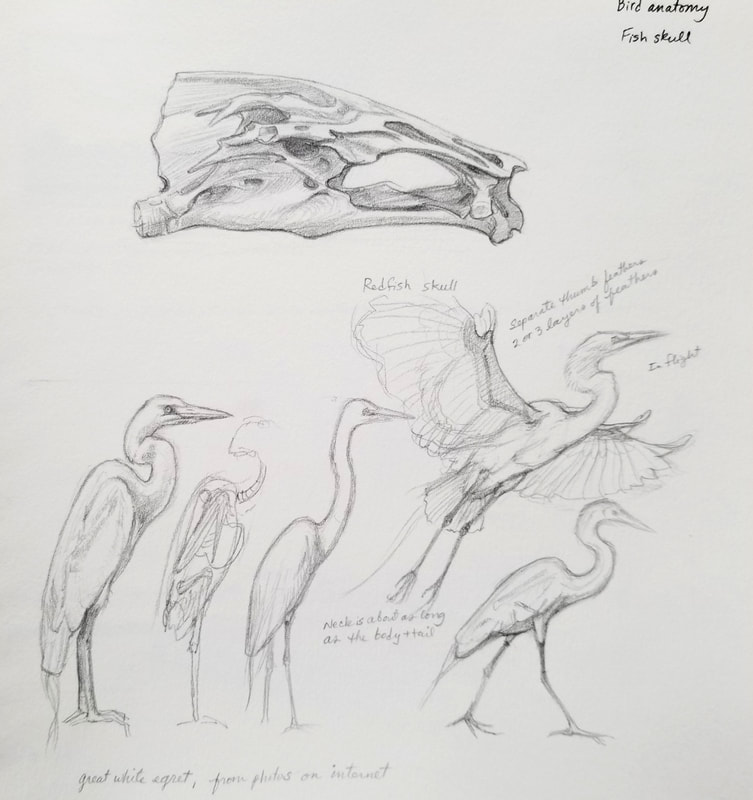

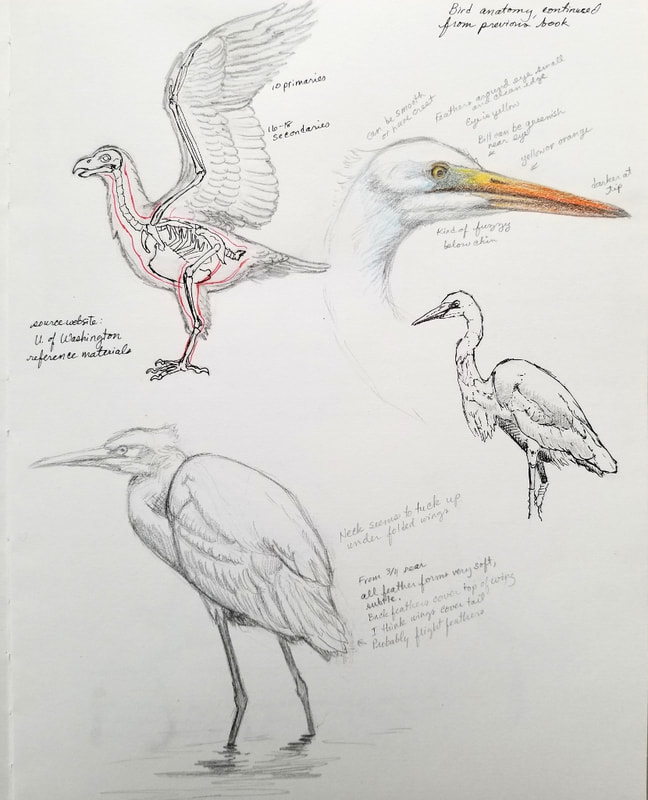

Sketchbook page, bird anatomy Sketchbook page, bird anatomy I've been living the rural life in South Carolina almost a year now, and it happens that for several of those months "social distancing" has been the recommended lifestyle anyway. Many people have commented that the safety rules resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic have brought them closer to nature as well as to home, which has given them some consolation and peace. My new home in the Lowcountry is ideal for that, and I am enjoying having nature observation opportunities as close as my front porch. I love animals of all kinds, and birds are especially fascinating. (I recommend the book Feathers: The Evolution of a Natural Miracle, by Thor Hanson, for as much as one could hope to know about the feather.) This is a rich environment for seeing birds, coastal species as well as woodland types. Several kinds of egrets, herons, laughing gulls, cormorants, etc. perch on our dock. A tall dead pine attracts eagles, osprey, vultures, wood storks, woodpeckers and owls. Bluebirds, pine warblers, Carolina wrens, painted buntings, mockingbirds, too many to count sing and flit around in the oaks, magnolias, palms and pines. I am just starting to learn about them and have a long way to go. Having done sketches from life and a few paintings that featured birds, I realized I needed to get a better grasp of their anatomy. Copying and drawing is the best way to learn! Here are a few pages from my sketchbook.

0 Comments

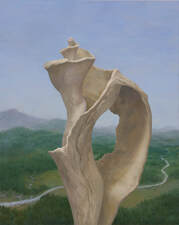

I was surprised to realize that my husband and I have been in Seattle for 20 years now. Living here has been a wonderful experience. The beautiful environment has been an inspiration for my art, and the people in the art community welcoming. I have participated in lots of exhibits at the Fountainhead Gallery and other spaces, and been impressed with the cultural scene here. In preparing to move back to the South and forge ahead with the next chapter in my life, I am enjoying pulling out of storage and reacquainting myself with paintings that didn’t find a buyer the first time around. Some have never been exhibited. I’m hanging them throughout the house and inviting art lovers to visit, browse and take advantage of this unique opportunity to purchase an artwork at a discount before I leave the Northwest. There will be a variety of sizes and subjects representing my various preoccupations. The larger paintings are framed or ready to hang, and I also have many unframed works for you to frame to suit your taste. I will have bins of figure studies to choose from, painted from the many lovely life models I have had the pleasure to work with. David and I will also offer for sale some artworks from our private collection, and artistic home furnishings and décor. Please contact me if you can’t make the event and would like a private showing. You can see some examples of artworks and prices here. Special Studio Sale: Sunday, July 14, 2019, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. 1416 N. 35th St., Seattle WA 9810  In anticipation of moving sometime within a year, I have been preoccupied, like many middle-aged people, with the familiar lament of how to winnow out possessions. Artists’ studios tend to fill up with not only finished and in-process artworks and art supplies of all types, but random inspirational objects and detritus that “may” come of use someday. With the current mania for minimalist lifestyles and Marie Kondo-style organizing in the zeitgeist, one can feel inclined to get rid of it all and return to the purity of the blank canvas. The hard part comes in finding new homes for objects and avoiding adding to the waste stream. Last year a friend told me about a Seattle organization called The Art of Saving Humanity that collects donated art supplies for the use of local immigrant and refugee artists. They have also mounted exhibits of the artists’ works. I was able to pass on to them many art supplies, used and unused, including a large set of pastels that had belonged to my grandmother. They also took a big batch of canvas-stretcher bars, frames, a folding easel and other items. I used to exhibit prints and other works on paper that had frames with sheets of glass, some quite large. I dismantled them and was thrilled to find a frame shop that took the glass, as it can’t go in the recycling bin. I posted a notice on Kelly’s Art List and gave away an antique French easel that had also belonged to my grandmother—feeling sad to do so, but glad someone else would use it, as I wasn’t. Even though I work slowly and have never been prolific, I find I have quite a few paintings in storage. I have been going through them with a critical eye and discarding those that don’t come up to my current standards. I keep representative drawings from different life stages, or those that have some special quality that makes me hesitate. It is still difficult to destroy a failed piece after spending an inordinate amount of time laboring on it. I remember being horrified as a freshman in college when an instructor described destroying an unsatisfactory drawing he had just spent eight hours working on (that seemed an awful lot of effort to me, then) and another telling the story of burning an entire year’s worth of work. To my younger self trying to build up a body of work, this was hard to imagine. Nowadays qualitative evaluation is easier, at least a few years after creation. If a large work on canvas is worth keeping, it can be taken off the stretcher bars and rolled for more compact storage. But some I have cut up and discarded, maybe keeping a few square inches of a well-executed portion as a memento. A few have found new life as backgrounds in my shadow-box assemblage pieces. I do have plenty of paintings in inventory that I am proud of, that didn’t sell when exhibited for whatever reason. Some are finding an enthusiastic audience and buyer at fund-raising auctions for art organizations and other worthy causes. A few others are finding homes after being offered for purchase to acquaintances in a targeted manner. I am not much good at business and marketing, having left sales to art galleries most of my career, but it is satisfying to match an artwork with an individual. (If anyone who happens to read this has been harboring a desire for a painting they saw in years past and wonders if it is still available, let me know!) The concept of having too much stuff brings up a painful issue—the dilemma of creating more unnecessary stuff (for art may be essential to an evolved society but not to sustain life) in a world that seems to have too much of everything and is running out of space to put it. I am a creative person and by nature feel compelled to make objects with my hands. Artists are advised to make lots of art, both to perfect their craft and to have plenty to bring to market. I have not gone overboard with this advice, but still sometimes fear I am contributing to an environmental crisis, and I worry that making more stuff is unethical. A few months ago, I brought up this doubt while attending a panel discussion on the habits of successful artists. Perhaps I didn’t phrase my question gracefully (I believe I used the word “crap” to refer to surplus art) but the artists sitting on the panel responded with something akin to outrage, as if even the topic was taboo, and quickly moved on. I guess as driven, self-confident artists this had never occurred to them. But at least one audience member came up to me afterward and told me of having the same concerns. Her solution had been to stop painting altogether and put her creative energies into writing. Many other artists are making art out of consumer discards, and exhibits devoted to recycling are becoming frequent. Then there are well-known artists like Andy Goldsworthy and John Grade whose sculptures are composed of, and degrade back into, the natural environment. It takes creativity to repurpose and to dispose of things in a thoughtful manner. Going forward I intend to be as mindful of avoiding waste in my studio as in my home, and try to make every mark on that blank canvas count. I decided to delve further into this socially-connected 21st century and join the many artists and regular folks posting photos on Instagram. It's a fun place for a visually-oriented person, with many thousands of members from all over the world viewing and sharing images, sorted by a system about which I am still learning. I am looking forward to perusing images posted by museums and galleries as well as by friends, artists I admire and art lovers. As for myself, I intend to share works in progress, studio views, glimpses of my working process, tools, inspirations and freshly finished artworks. Since I still lack a smartphone, you aren't likely to be confronted by pictures of my food or face. Follow me here: Instagram.

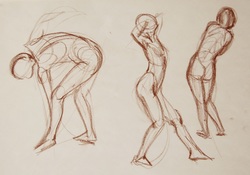

Many artists consider representing the human form to be the ultimate challenge, and I am one of them. Artists who specialize in portrait and figure painting strive for years to master it, and have to keep practicing just as an athlete has to exercise. Even artists who normally exhibit only landscape, still life or abstract art will return to sketching the figure from time to time. It’s hard to find friends who are willing to sit still and be stared at for hours, and hiring a professional artist’s model is expensive. We are lucky in Seattle to have several group studios at which to practice drawing and painting from a nude, portrait or costumed model on a regular basis. I like to go to the Open Studio sessions at Gage Academy of Art when I can. They commonly schedule short pose or long pose (3 hour) sessions almost every day, and are open to artists on a drop-in basis for a reasonable fee.  At short pose sessions, poses range from less than a minute to 20 minutes. Quick drawings are called “gesture drawings” and the goal is to capture the flow of the pose, the feeling of the weight and pull of the model’s muscles, in a few lines. The artist should almost become the model. These are valuable to train the eye and hand to respond intuitively to the subject. In the longer poses one can spend more time measuring proportions and angles, and then adding details and shading, but I believe the initial gesture sketch is still the most important element in capturing the gestalt of the person before you. Sometimes an art school or group of artists will hire a model to repeat a pose for an extended number of sessions so they can complete a more resolved study. I have attended a few of these, and use the sessions to try out various approaches to painting form—systematic classical processes like drawing first, proceeding with monochrome paint, then layering of color, etc.; or direct processes such as alla prima, with brush drawing and using full color from the start. Often I find myself diverging from my initial plan as the painting evolves, from lack of patience or changing goals. Painting with a group of other artists and responding to the figure in front of you is different from working alone in one’s studio. There is the camaraderie of the other artists, with whom you can share painting tips, and there is the personality of the model. Some are more talkative and open about their lives, and others are strictly business. I think of him or her as an actor on stage, and for a successful painting, I must imply a mood or a bit of a story to make the scene interesting. A painting or drawing of a figure model “just” standing or sitting there can be a fine thing if skillfully rendered, but it needs something special to transcend being an exercise in anatomy and to draw in the viewer if it is going to be exhibited. Some artists are able to do it with beautiful marks with the pencil or paint, or an interesting perspective; others can find something special in the expressiveness of the face or pose.  Earlier this year I attended a series of morning “reserved easel” sessions at Georgetown Atelier to paint a lovely young model. My strategy for this study was to do a drawing at the first session, getting the feel of the pose and deciding the composition of the painting. Next I loosely sketched the composition on a small linen-covered panel in charcoal and began to paint. I decided to keep the study monochrome until the shapes and values were fully resolved, and for this I used burnt umber and lead white. I spent two or three sessions on this; the lighting was challenging since my back was to a bank of large windows and the light and shadows changed dramatically as the sun rose and storms moved through, conflicting with the strong lamp above the model. I practiced using thicker paint and looser brush strokes, fighting my tendency to over-blend. During the final couple of sessions, I started adding color, but kept it muted, as there was not a lot of color in the scene. I started this study with no expectations other than a learning experience, and I am pleased with parts of the resulting painting. Right: Young Woman in a Shadowy Room, 16” x 12”  A few times I have hired a model to come to my studio and pose for more complex paintings. I used the model as an actor in a scene that had implied narrative, which was not fully pre-conceived but evolved as I worked with the model and then added background and other elements without her presence. In the end, the final product may not even look like the model as it takes on a life of its own. Two of these paintings that I made a few years ago will be hanging in an exhibit called “Figuratively Speaking” at Ida Culver House Broadview (12505 Greenwood Ave. N., Seattle), curated by June Sekiguchi. There will be a reception with wine, hors d’oeuvres and music on May 19 from 3:30 to 5:30 that is open to the public; please RSVP to 206-361-1989 by May 16 if you would like to attend. The exhibit will be up, in the lobby and public areas of the building, until September 11, 2016. Left: Sleepwalker, 2006, oil on canvas, 28" x 22"  Cloudy With Chance of Teardrops, oil, 24" x 30" Cloudy With Chance of Teardrops, oil, 24" x 30" Every now and then, when perusing social media, I will come across a story or video about a blind artist. This brings up questions immediately: How do they do it? And also, why? Is it to show us the blind can do anything the sighted can, or is it a manifestation of creativity that can’t be expressed any other way? It’s an interesting topic to think about for a visually oriented person. I am taking part in a group exhibit at the Mount Baker Neighborhood Center for the Arts that includes at least one blind artist. This relatively new non-profit gallery in the Mount Baker ArtSpace Lofts building has a mission to bring together artists of all levels, and provides opportunities for artists with disabilities and the under-served community. I heard about their exhibit, “Flowers, Flores, Ubaxa,” through a call for art notice, and thought it would be an opportunity to put back on view one of my flower pieces from a few years ago. I occasionally participate in exhibits in neighborhoods in the greater Seattle area, in part because I have a good inventory of paintings and it’s gratifying to have them appreciated, and in part to explore and to meet the dedicated people working to put these shows together for their communities. When applying for this exhibit, I was intrigued to see they requested a visual description of the art along with the image, not the more esoteric artist’s statement. When I dropped off the painting in Mount Baker, I met the director, Barbara Oswald, who has very little sight, and she introduced me to a blind artist who would be exhibiting a painting for the first time. The artist had made a small acrylic painting of poppies floating on a blurred, textural background. The colors were unusual but harmonious, the contrast good, and she had achieved a delicate translucency in the petals. I learned from a casual search on the Internet that many people classified as blind can see a bit of light and form, which answers some of my questions. But there is one well-known blind painter in Turkey, Esref Armagan, who was born completely unsighted, and is self-taught. His work could be characterized as child-like or primitive, but the work of the late British artist Sargy Mann is quite sophisticated, despite increasing blindness that started early in his career. At the end of his life he was painting completely blind, by touch. As he said, so much of art goes on in the head. I also learned of a sighted artist, Roy Nachum, who incorporates poetic messages in Braille into his large oil paintings. The striking, realist images in minimalist color schemes have bumps sculpted under the paint so they can be read by touch. I wonder if, since color absorbs and reflects light at different wavelengths, if a method could be devised to experience color on a surface by variations in temperature. My own eyesight is not strong; I have worn glasses since second grade. A couple of years ago, I attended a touring Blind Café, where in a totally dark church basement, diners ate and listened to a concert, assisted by blind servers who shared their experiences with us. Those of us with normal vision are amazed by the skill with which the blind cope with everyday life, but they prefer we not be. When I try to imagine what I would do with my life were I to become blind, I assume I would concentrate my efforts on sculpture and/or music. Painting is difficult enough when I can see. But maybe it would be freeing, and take away some of the value judgement, to try it with the eyes closed. The exhibit “Flowers, Flores, Ubaxa 2016” will be at Mount Baker Neighborhood Center for the Arts April 1 through 28. There will be two receptions to meet the artists, Friday, April 1, from 4:30 to 7:30 p.m. and Sunday, April 3, from 3:00 to 6:00 p.m. The gallery is located near the Mt. Baker light rail station at 2919 Rainier Avenue South. |

AuthorHere I will keep you up to date on my exhibits and other artistic endeavors. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed